In the last decade, innovation and economies of scale have dramatically reduced the cost of clean technologies. But this success story is under threat from the availability and costs of the critical raw materials that underpin this global transformation. In this blog, we look at how critical minerals extraction is restricted by economics, show what governments around the world are doing to address the problems, and suggest a new model for critical minerals investment.

Could a lack of critical minerals de-rail the green revolution?

To look at the growing influence of raw materials on clean technology costs, consider the case of cathode materials. These are essential for lithium-ion batteries and include critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt and manganese. In the middle of the last decade, these accounted for less than 5% of battery pack costs but now that share has risen to over 20%.

The simple answer to reducing raw material costs is to increase supply. However, it is not that easy to increase supply given how hard it is to extract these minerals in the first place, and the constantly increasing demand means supply is always playing catch up.

What’s going wrong with the current market model

The major problem for critical minerals is not that they are rare, but rather the current economics of mining do not encourage investment to extract them from new resources.

The first problem is an over-concentration of resources in a small number of countries, particularly in the processing of minerals. In general, the more concentrated the supply of raw materials, the greater the risk of temporary or permanent curtailment of supply, and the more volatile the costs.

Add to this the strategic nature of these minerals, and the growing desire of many governments to control the export of their resources, and you create uncertainty in supply with markets overly susceptible to political forces.

To increase supply requires investment. There are positive trends such as the significant uptick in spending from the world’s leading mining companies, and analysis of newly announced projects suggests that supply could meet the requirements of announced pledges by governments. But this still falls far short of what would be required for actually hitting net zero emissions.

More investment is needed but the risks are acting as a deterrent for companies and institutional investors who are naturally risk averse. The longer-term nature of critical minerals projects (it can take 16 years to develop projects from discovery to first production) means it can take longer to see a return, while the volatility of markets over time makes that return harder to calculate.

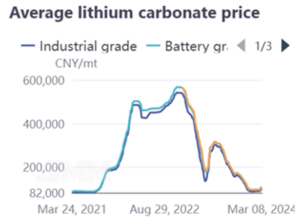

Taking Lithium as an example, data from our partners at Shanghai Metal Markets (SMM) shows that lithium has experienced significant price volatility in recent years. In the past three years, the price of lithium has experienced significant growth before peaking in November 2022, and then entering a downward phase. According to SMM these price dynamics are created by the interplay of macroeconomic factors, market speculation, and evolving lithium uses.

These risks are putting off investors who have traditionally focused on short-term yields rather than longer-term value and growth. It is also true that investors favour what they know, in part explaining the continued support for fossil fuel projects of around $1 trillion annually going to companies supporting new development projects[1].

Governments are using policy levers to stimulate investment

Given the strategic importance of critical minerals, it is not surprising that governments around the world are using policy levers to support their mining or manufacturing sectors. Examples include:

- Australia offers loan guarantees or preferential loans as a complement to private financing to help launch projects involved in extracting or processing minerals for export.

- The establishment of the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation to provide funds to support exploration activities, promote development of extractives project and administer the national stockpiling systems for both oil and metals.

- The US Inflation Reduction Act provides a production tax credit for producers of critical minerals and introduces demand-side incentives for electric vehicle buyers who choose cars with domestic mineral production.

- Canada’s 2022 Budget earmarking $1.5 billion to bolster projects in manufacturing, processing, and recycling of critical minerals.

Is it time to think differently?

Incentives and loans can help the market grow but given that low supply can derail the shift to a net zero, is it time for government to take a bigger role in the market? Examples from sovereign wealth funds suggest it is time to think differently. These include:

- Ghana’s sovereign wealth fund investing $33m in the nation’s first lithium mine in 2023.

- Saudi Arabia’s PIF and Saudi Arabian Mining Co. (Maaden), purchasing a 10% stake in copper and nickel producer Vale Base Metals for $2.6bn.

- Barrack Gold courting PIF around investing in a copper mine in a western Pakistan province plagued by insurgents — the kind of hazardous environment that most investors would steer clear of.

- An Australia-UAE free trade deal that is expected to include the UAE sovereign wealth fund investing in the extraction and processing of Australian critical minerals.

Sovereign wealth funds benefit from longer-term investment mandates and the longer a fund’s investment horizon, the higher its capacity to take on investment risk. This ‘patient capital’ allows them to weather short-term market fluctuations and focus on the strategic value and long-term potential of investments. This patient approach is particularly useful for seeing out the cyclical nature of costs in the industry highlighted earlier.

While not all sovereign wealth funds will have the deep pockets of PIF in Saadi Arabia, there are lessons to be learned for governments seeking to invest in the exploration, extraction and processing of critical minerals. These revolve around longer-term thinking about risk and bringing diplomatic and political support to play to avoid miners facing sudden regulatory changes in foreign jurisdictions.

The future of critical minerals

Sovereign wealth funds are likely to shape the future of investment in critical minerals and place their nation-state as powerbrokers in the future low carbon economy. As China and the US continue to eyeball each other across multiple sectors it is countries in the Middle East such as Saudi Arabia that emerge as the alternative for critical mineral suppliers and buyers.

Other countries that want to be major players in this sector will need to rethink their appetite for risk and investment.

Keeping an eye on critical raw materials prices

Before reconsidering your risk and investment appetite, it’s especially important to keep tabs on the prices of these critical raw materials.

Our partners at Shanghai Metal Markets (SMM) – Steel,Aluminum,Nickel,Rare earth,new energy,Copper Prices Charts and news-Shanghai Metals Market, which had entered the metal market at a very early stage and have been active for over 25 years, becoming leading integrated platform in the field of nonferrous and ferrous metals.

Organized by SMM, one of the China biggest new energy and battery industry expo – https://clnb.smm.cn/en/home?fromId=108. You can network with more than 200 industry experts, company leaders and government officials. With more than 10 new energy industry forums, you could know the industry better and wider.

[1] https://unctad.org/es/news/se-necesita-un-cambio-urgente-de-billones-de-dolares-para-alinear-las-finanzas-globales-con